Commentary

Protected: What is co-living, and why is it such a big deal?

Protected: Hispanic homebuyers are the future of the U.S. housing market

Protected: Gerhard Mayer: U.S. Urban Planning Needs Complete Paradigm Shift

Protected: Offering Childcare at City Meetings May Be Key to Diversifying Civic Engagement

In the News: 2018 Was the Year of the YIMBY

A milestone upzoning plan in Minneapolis capped a year that saw pro-housing forces duel NIMBYs in cities nationwide.

Other facets of the plan are drawing critical acclaim, too. The policy eliminates off-street minimum parking requirements, making Minneapolis the fourth city to make such a move. (San Francisco pulled the trigger earlier in December, while both Buffalo in New York and Hartford in Connecticut did so in 2017.) Reason hailed Minneapolis 2040 as a victory for free-market deregulation (even as it pooh-poohed an inclusionary zoning ordinance that encouraged developers to set aside units for low-income families).

Steep odds for state-level upzoning are also the rule in California, where Scott Wiener, housing champion and state senator, has introduced legislation to repeal a constitutional amendment that restricts low-income housing, as well as another bill to boost denser development near transit. For the latter piece, this is Wiener’s second bite at the apple, after the similar State Bill 827 went down in flames in April. No, 2018 wasn’t an unambiguous victory for housing advocates.

State government likely presents more challenges than opportunities for zoning reform. Texas, for example, passed a bill in 2015 that preempts any municipality from enacting local protections for Section 8 voucher holders. Landlords who discriminate against renters with housing aid drive segregation patterns today. If Atlanta succeeds in passing reforms to promote granny flats, curb minimum parking requirements, and legalize new apartment buildings (all changes endorsed by the city’s zoning board), there’s always the threat that the Georgia state legislature will interfere, as it has done or threatened to do with local laws regulating tobacco, Airbnb, the minimum wage, and more.

Instead, local leaders hit on successful ways for overcoming the value-action gap—a wonky term for the phenomenon seen when homeowners in progressive neighborhoods post yard signs welcoming all peoples even as they oppose nearby housing developments. Going forward, there are proven tactics for bridging the value-action gap and solving for the ABCs of social change—attitude, behavior, and choice. Minneapolis finally got the damned thing done, and others will follow.

Finally, 2018 marked the Year of Our Lord when NIMBYism went from a seemingly unstoppable force to a figure of mockery. End your year with one Minneapolitan’s delightful zoning parody: “I Was Radicalized by Minneapolis 2040.”

“As I drove from 50th to Lake Street I was subjected to the type of pure urban obscenity that occurs when single family houses mix with apartment buildings. There were duplexes, triplexes, plexplexes,” writes Kristopher Kapphahn, a Twin Cities biostatistician. “They were all just nestled right in among innocent single-family homes. And it was awful. Anyone who has taken Bryant through South Minneapolis knows what I now newly knew: it’s the very definition of urban hellscape.”

Article: Why Cities Must Tackle Single-Family Zoning

In my neighborhood in San Francisco (or, more accurately, my parents’ neighborhood) there’s a plan afoot to build 42 units of new housing in two parking lots, just steps from a light rail line. Thanks to the city’s inclusionary zoning laws, 18 to 20 percent of those units must be offered at below market rates, on streets lined with single-family homes worth around $1.5 million, and renting for around $5,000 per month, according to Zillow.

Construction could still be years away, due to the city’s byzantine approval process. But the neighbors are already buzzing about the plan, expressing fears that the development won’t fit the neighborhood and preparing demands to scale the project down. It’s Bay Area NIMBYism-as-usual—except that my neighbors are progressive enough to blanch at that now-loaded term. They’re still YIMBYs, as one writer on our local listserv insisted—just the kind whose “yes” to new housing is a bit more qualified.

Convincing—or forcing—the homeowners who rule these neighborhoods to accept new housing that is not consonant with the existing fabric of million-dollar homes is an oft-overlooked front in America’s housing wars, and one that could have a huge structural impact. Adding dense or below-market-rate apartments in high-income neighborhoods close to job centers allows more people to live and commute in an environmentally friendly manner, increases economic mobility, and counters the shameful legacy of segregation.

In Generation Priced Out: Who Gets to Live in the New Urban America, San Francisco tenant activist Randy Shaw paints a picture of a nation beginning to wake up to its housing crisis, but unsure of what to do about it. For years, the discussion around housing affordability in big cities has focused on gentrifying neighborhoods like San Francisco’s Mission District and Brooklyn’s Williamsburg. But according to Shaw, not enough attention is being paid to the wealthier, usually single family home neighborhoods that have effectively walled themselves off from all new housing construction, creating a sort of spatial class privilege that is rampant in America’s most progressive cities. “These high-opportunity neighborhoods must serve more economically diverse residents,” he said in a recent interview in CityLab. “[C]ities that claim to promote inclusion cannot just relegate the non-rich to economically segregated parts of town.”

***

Shaw is a unique breed of housing activist; as the director of the Tenderloin Housing Clinic, he’s long fought for tenants’ rights and affordable housing, but he’s also a strong advocate for building enough market rate housing to keep up with job growth. For decades, and to this day, American cities have not done enough to address either issue, he contends, but some have done a better job than others with particular strategies.

While Shaw calls San Francisco “a cautionary tale of unaffordability,” he also says it “does the best job of every major city in protecting tenants and its rental housing stock.” Of course, he would say that: Shaw is the architect of many of those policies. But it is true that the city has significant tenant protections, including very low rent increase caps for rent control tenants and strong restrictions against the demolition or combination of existing affordable units. The city has also pioneered innovative policies, like its free legal representation program for tenants facing eviction, and a small sites acquisition fund that purchases properties occupied by at-risk tenants and removes them from the speculative market.

But Seattle and Denver are stymied in their efforts to protect existing tenants by state policies and preemptions. Both Washington State and Colorado (along with the majority of states) bar cities from enacting rent control. In California, too, rent control remains limited by a state law, as voters failed to pass Proposition 10, which would have allowed the state’s cities to expand rent limits. In Washington, just cause eviction laws are also hampered by preemption, and in California, the notorious Ellis Act results in thousands of evictions every year.

In the face of these obstacles, and the lack of financial support for housing from state and federal governments, cities are trying to make the most of the tools they have. Portland, San Francisco, and Alameda County (which contains Oakland and Berkeley) have all passed affordable housing bonds in recent years, and Austin and California just passed housing bonds this election.

In addition to building more housing themselves, the biggest thing cities can do to improve housing affordability is change zoning laws. Inclusionary zoning, which requires developers to reserve a certain percentage of new units as affordable, has become more popular in recent years (although some states, like Colorado, also preempt it). But not all inclusionary zoning is created equal: New York’s 2016 law only applies to projects that request zoning variances, even though 35 percent of the city’s land area, including many low-income areas, had recently been rezoned. Inclusionary zoning in D.C. and San Francisco applies to all projects of a certain size.

In concert, increased supply of affordable and market-rate housing, along with strong tenant protections, can stabilize gentrifying communities. Evictions in San Francisco decreased by 21 percent between 2016 and 2017, and another 12 percent between 2017 and 2018. And in the Mission District, the Latino population actually increased by 1,500 between 2011 and 2016, following years of declines. Shaw attributes this trend to an increase in both nonprofit affordable housing and inclusionary units—and, somewhat more controversially, to the “by any means necessary” tactics employed by anti-gentrification activists. By protesting and threatening to hold projects up in court, activists in neighborhoods like the Mission and Los Angeles’ Boyle Heights have negotiated for more affordable units in many projects, and likely discouraged speculators.

These tactics are productive because their practitioners are still pro-housing: They want to maximize the amount of affordable housing in their neighborhoods. But in single-family-home neighborhoods, residents tend to be against any kind of new housing, especially if it’s affordable. In San Francisco’s affluent Forest Hill neighborhood, residents successfully killed a 150-unit development for low-income seniors, a stone’s throw away from a subway station, arguing that it would attract mentally ill and drug-addicted people. Shaw’s book is full of similar examples from around the country of homeowner groups opposing new housing on baldly elitist grounds.

The other tactic frequently employed by homeowners—saving “neighborhood character”’—is often a means to the same end. “Character” must be understood as not only visual, but also demographic. In cities like San Francisco, preserving the status quo for a single-family-home neighborhood often “means maintaining it as a neighborhood where future residents must be rich,” Shaw writes. Another critique levied by those who do not want their neighborhoods to change is that new housing construction in expensive urban markets is inevitably luxury housing. But this argument falls flat when nearly all existing homes are already luxury housing: According to a recent Trulia study, a staggering 81 percent of homes in the San Francisco metro and 70 percent of homes in the San Jose metro are worth more than $1 million. Conveniently, single-family-home zoning also functionally prevents the construction of nonprofit affordable housing, or the below-market-rate units that are generated by inclusionary zoning.

The irony is that the communities most vehemently opposed to new apartment buildings—cities like Portland, Oregon, and Cambridge, Massachusetts—are among the most politically and socially progressive in the nation. They are “trapped in the framework of past urban renewal fights,” Shaw writes, when historic, low-income neighborhoods were demolished willy-nilly, and suburban-style urban development was viewed by many as a more environmentally friendly style of living. And so are land use regulations, which responded to citizen outcry in the ‘60s and ‘70s by downzoning many neighborhoods, which prevents new apartment buildings (but permits modest single-family homes to be converted to McMansions). Today, 42 percent of Portland, 57 percent of Seattle, and 78 percent of Los Angeles are zoned exclusively for single-family homes.

Times have, in fact, changed since the 1970s, but getting liberal urban Boomers to understand that will be a massive undertaking. As Shaw’s title suggests, this is nothing short of a generational project that should engage YIMBYs, anti-gentrification activists, and progressives of all stripes who recognize how intersectionally damaging single-family-home zoning is.

To bolster this progressive stance, upzoning should always be accompanied by inclusionary zoning. But a more radical approach, and one that would really give coastal liberals pause, would to be to upzone only neighborhoods above a certain median income threshold, or those that have historically excluded people of color. Upzoning these areas to allow more mixed-use, mixed-income development “opens up middle-class housing opportunities in these otherwise off-limits communities without any risk of displacing low-income residents,” Shaw writes. Good luck arguing against that, my silver-haired comrades.

Article: Dark Store Fight is Spreading

Discount center: As the “retail apocalypse” rolls on, many cities are struggling to make up for the lost tax revenue they’ve come to expect from brick-and-mortar businesses. As it turns out, some surviving big-box retailers—like Walmart and Target—have found a way to trim their own expenses in a way that only amplifies cities’ budgetary pain. And they are focusing their efforts on a forum that few residents might notice: property tax assessments.

It’s called “dark store theory,” and it’s essentially a novel argument that bustling big boxes should be taxed more like vacant “dark” stores. That means tax assessments value these open, functioning outlets as it they were the shuttered “ghost boxes” that have become increasingly common on the fringes of towns and suburbs. With appeal after appeal, retail giants are succeeding in persuading tax assessors and judges to accept these lower valuations.

CityLab’s Laura Bliss went to the epicenter of this theory, Wisconsin, to meet the mayors, assessors, and lawyers dueling over dark stores. Since 2015, the Badger State has seen 230 appeal cases in 34 counties, many as repeat appeals on the same properties. These appeals can add up to millions in tax refunds across towns. In the wake of yesterday’s Amazon HQ2 news, here’s a different story about the shifting fortunes of the retail landscape, the creative ways big companies avoid taxes, and the handouts towns keep offering to lure them in. Read Laura’s report: After the Retail Apocalypse, Prepare for the Property Tax Meltdown

Protected: Article: SF supes OK rezoning underused lots to allow more affordable housing in SoMa

Protected: Article: The tenant-landlord relationship is going digital

Why Vulnerable Populations Need Compassionate Cities

Janet K. of Memphis is a widow living on fixed income and Social Security, and deals with health issues related to her age. She’s struggled with tree roots invading her sewer system for years and knew something had to be done.

Unfortunately for Janet, she simply didn’t have the $3,000 needed for the repair. Like many Americans unsure of what to do with an emergency repair, Janet turned to her church, family, and prayer. Fortunately, her supportive local community helped her to rebuild.

The effects of a financial shock, such as a major car repair or a sudden loss of income, can be especially difficult on the elderly. According to the Urban Institute, “As a nation, and within our cities, our population is aging. The number of Americans over 65 will double between 2000 and 2040, while the number of adults over 85 will quadruple over that period. And there are many within this aging population who have not adequately saved to prepare themselves for the expense associated with increased life expectancy and aging in place.

Poverty in American Communities

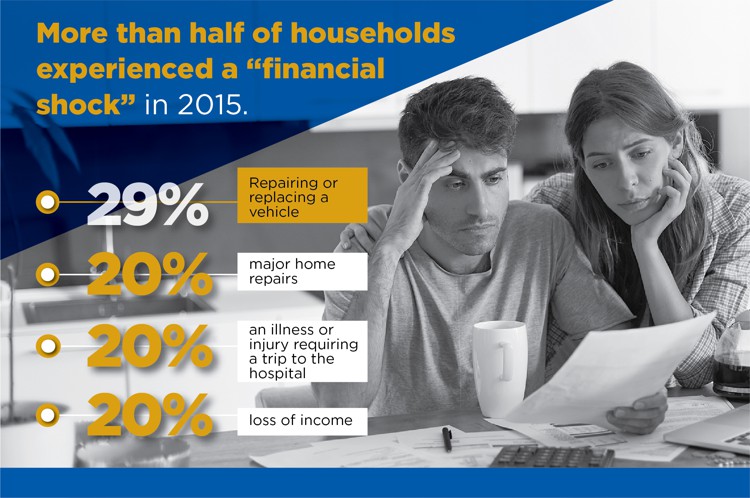

Poverty in the US has changed little over the past four decades. Currently over 43 million people, one of every seven Americans, live below the poverty line in urban and rural communities. These households are extremely vulnerable to the effects of a financial shock, caused by expenses or lost income that families do not plan for; such as from job loss, illness, injury, death, or a major home or vehicle repair.

A study on the future of equity in cities recently published by the National League of Cities indicated that while cities are benefiting from the “positive outcomes of wealth flooding into metropolitan regions, they also feel the negative impact on community members of varying income levels – particularly, those at the bottom that face increased housing prices, greater need for social services and growing concern for community safety.”

Organizations such as the National League of Cities and PolicyLink are advocating for an equitable agenda when it comes to urban development plans, recognizing that well-planned urban infrastructure can have a positive impact on communities often left behind. According to Anita Cozart at PolicyLink, “infrastructure is vital for sustaining and reinforcing community. The networks, roads, schools, drinking water, sewer systems, facilities, and properties that comprise public infrastructure define neighborhoods, cities, and regions.” And city planners don’t have to go it alone. Cozart says “there are also emerging leaders in the philanthropic and business sectors who are embracing the agenda.”

Over 500 cities across North America have decided to partner with the National League of Cities (NLC) Service Line Warranty Program, administered by Utility Service Providers, to offer an affordable solution to their residents, a solution that complements the infrastructure planning needed to build vibrant cities.

The NLC Service Line Warranty Program is a good example of the private sector contributing to infrastructure improvement. Requiring no investment of municipal dollars and little in the way of municipal management, collaborating with this NLC program enables municipalities to educate and protect homeowners without the extensive logistical and administrative challenges that can distract from their core missions.

The Average American is Unprepared for Financial Shock

Adam and Jennifer F. loved the first home they purchased a historic 100-year-old house in a quiet Wichita, Kansas neighborhood. But when their private sewer line failed, the line that carries sewage from their home to the city’s main sewer line in the street, they were at risk of real financial hardship.

The cost to replace and re-route the line would be at least $7,000 dollars – a significant portion of the couple’s annual income. Since they were unable to afford the needed repair, a local contractor who works for the NLC Service Line Warranty program approached Utility Service Partners to see if the job could be covered under their HomeServe Cares program. These programs can help younger people who haven’t yet built up the savings or credit to afford unexpected home repairs.

When researchers at the Federal Reserve asked the average American whether they could handle the cost of an unexpected home repair project, the answer was simple: no. The Federal Reserve Report on the Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households in 2017 found that 4 out of 10 Americans can’t afford a $400 emergency expense and would have to sell something or take out a loan to cover it. These types of financial shocks can be catastrophic to already vulnerable households as well as those in the shrinking urban middle class, and they happen with alarming frequency.

Aging Private Infrastructure Contributes to Financial Pressures

Paul T. of Waukegan, Illinois, a 96-year-old World War II and Korean War veteran, is living his retirement years surrounded by his family. He shared his home with the children he had raised there and his grandchild. Having his family around him helped the older veteran address health issues, including asthma and being on oxygen.

When’s Paul’s plumbing system choked and backed up, Paul’s unfinished basement filled with six inches of gray water, and everything in the home’s sewer system ended up in the basement.

Fearful for their father’s health and worried about the possibility of toxic mold, the family sent Paul to live with a nearby family member as they tried to address the issue – and how they would pay for the $3,000 repair bill.

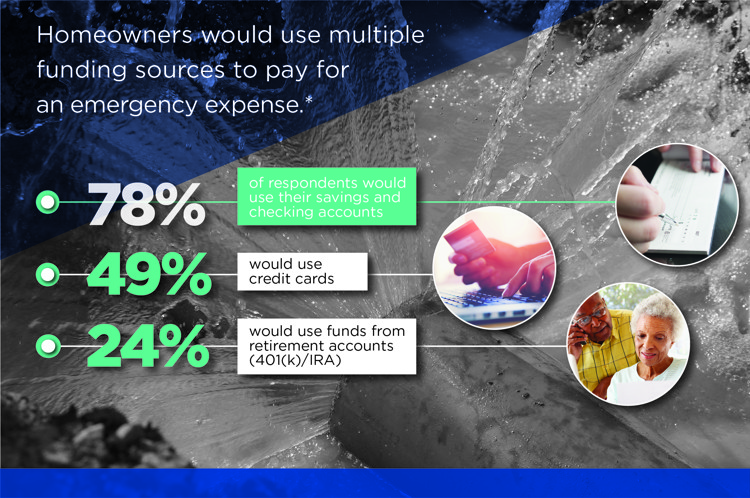

When an unexpected financial shock is added to the mix, the elderly may deplete already insufficient retirement savings. According to a survey, when faced with an emergency expense, about a quarter would use early withdrawal from retirement accounts, such as a 401(k), or an individual retirement account (IRA), and this was more likely in households with lower incomes.

Embracing Equitable Agendas in City Leadership

Even with cities making efforts toward equitable infrastructure planning, many residents are still at risk for a significant financial shock due to the aging private infrastructure that brings fresh water into their homes and carries sewage out. Breaks or leaks in private side water or sewer lines can result in repair bills into the thousands of dollars. These leaks and breaks in water and sewer lines, the lines that run between a home and the city’s main line, are far more common than most people assume.

According to a recent study by HomeServe USA, a leading provider of home repair solutions and parent company of USP, that administrates the NLC Service Line Warranty Program, 51% of homeowners reported having a home repair emergency in the past year alone.

USP and HomeServe execute over 400,000 repairs each year and are therefore keenly aware of the prevalence of these emergencies as well as the financial hardship they can cause for unprepared homeowners. “We want to work with our city partners to find solutions to real issues,” said John Kitzie, CEO of USP.

Thus, the HomeServe Cares program was created as a public commitment to aid disadvantaged homeowners who are faced with a service emergency and don’t have the resources or capability to deal with it. The program leverages the company’s most valuable resources: the outstanding network of over 1,100 local contractors, to deliver services to their neighbors in need. Like Paul T. in Waukegan.

A local contractor who is part of the network servicing customers of the NLC Service Line Warranty Program alerted USP to the family’s troubles. The HomeServe Cares program covered the cost of the emergency, after-hours dispatch to pump the grey water out of the basement and clean out the sewer line. Once the basement was free of water, the NLC SLWP also arranged the installation of a new water heater, restoring hot water to the family’s home – all of it without cost to Paul and his family through the HomeServe Cares program.

Caught without a safety net, vulnerable populations of varying ages and income levels, like Paul and Adam, are often left with nowhere to turn.

City Leaders Step Up to Help Vulnerable Populations Rebuild and Repair

Many innovative city leaders agree that these stories demonstrate the need for equitable infrastructure planning to include a component to cover the private side of aging infrastructure. Low cost emergency home repair plans help financially vulnerable populations prepare for potential breaks and leaks to the service lines that provide them with fresh water. These programs also serve to educate homeowners about their responsibility for repairs to these lines. In all of these cases described, an inexpensive monthly repair service plan would have provided the homeowners with immediate access to repair or replacement of the damaged water and sewer lines.

Mildred Crump, former City of Newark, New Jersey councilwoman, was keenly aware the City was experiencing a steady increase in water infrastructure challenges and problems.

In the City of Baltimore, city leaders knew if the city officials were struggling with infrastructure problems on the public side, then so were residents. “We needed to find a solution for our residents, because they could be faced with unexpected, and high, repair bills,” Shonte’ Eldridge, Baltimore City’s Deputy Chief of Operations, said.

Over the past 15 years, the combined power of USP and HomeServe have performed 2.9 million repairs or replacements to critical home systems, spending more than $775 million. But these repair programs are primarily introduced to homeowners through partnerships with cities or utilities, and many city officials remain unaware of the urgent need for them or are unconvinced their residents need them.

“Throughout those couple weeks, I shared my story with lots of different people, and I was shocked to learn how many people have similar issues. Many feel the same way I do,” Adam said. “If I would have known of the availability to purchase a low cost repair plan, I would definitely have purchased it”

When a city embraces a partnership with the program, the investments will address both the issues of aging infrastructure and equitable progress in their cities, helping ensure that vulnerable populations have access to the home repair resources desperately needed to keep them in their homes.

Citylab Sponsor Content:

Court of Appeal Affirms Trial Court’s Decision on Martin Expo Town Center Project

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Protected: Article: The Neighborhoods That Offer a ‘Bargain’ on Upward Mobility

Article: The Urban Land Institute’s annual look at the year ahead focuses on technology and transformation at an uncertain moment

Protected: Article: On Yelp, Gentrification Is in the Stars

Article: Parcels, Taking, and Environmental Protection in Murr v. Wisconsin

Earlier this year, the U.S. Supreme Court turned its attention to property boundaries in a case that adds to its corpus on the Takings Clause of the Constitution. In Murr v. Wisconsin , a family challenged a regulation that fused or “merged” its adjacent parcels of land, preventing them from being sold separately. The family claimed that the restriction amounted to a government “taking.” (Murr , 137 S.Ct. 1933 (2017).) …

Read the article in the American Surveyor, October 2017 Parcels, Taking, and Environmental Protection in Murr v. Wisconsin

Written by Lloyd Pilchen who is a municipal, land use, and environmental lawyer with Olivarez Madruga Lemieux O’Neill LLP in Los Angeles. Pilchen serves as city attorney for the City of Ridgecrest and assistant city attorney for the cities of El Monte and San Gabriel in California.

Protected: Article: The ascent of climbing gyms, and battle for post-industrial real estate

Protected: Article: Finding the Untapped Potential of Alleys

Protected: Article: Action Outside a Public Meeting, What Could Possibly Go Wrong?

Protected: Article: Michael Woo – Is There Such a Thing as Too Much Democracy? Challenges to Building Affordable Housing in LA

Protected: Article – Carlyle Hall Opines on LA City’s Forfeiture of Local Control Over ADUs

Protected: Article: Helen Leung Argues ADUs Make a Positive Contribution in Combating CA’s Housing Crisis

Protected: Article: Bob Wieckowski on His SB 831 and the Need for ADUs

What’s Happening in Planning 2013

“The City of Los Angeles is at a pivotal point in its history. Over the last ten years, many positive changes have taken place. With thousands of new lofts and LA Live, Downtown is now thriving. The revitalization of Hollywood is a success story that shows what visionary leadership and strategic redevelopment can accomplish. All across the City, mixed use development that combines multi-family housing with ground floor commercial is the new norm. With the passage of Measure R in 2008, the region is making an unprecedented investment in its rail transit system. Much as the freeway system defined Los Angeles in the 20th Century, the creation of a true regional transit network has the potential to redefine Los Angeles in the 21st. While the City faces many challenges, from creating new jobs and building enough affordable housing, to repairing our streets, maintaining effective public services, and providing adequate infrastructure, there is reason for optimism.

On January 1, 2014, a new Department of City Planning and Development goes into effect that will unify the City’s planning, development services, and permitting functions. Along with the new Economic and Workforce Development Department, which was launched on July 1st of this year, the potential to improve the City’s business climate by eliminating bottlenecks and improving customer service has never been greater. Coordinating the work programs of these two Departments can create public-private partnerships and synergies that will facilitate the creation of thousands of new high-tech and green jobs, laying the foundation for a 21st Century economy. BuildLA, the long-anticipated web-based permitting system, will revolutionize the way the City does business with everyone who invests and builds in Los Angeles, from homeowners and small business owners to large corporations and developers.”

Table of Contents of What’s Happening in Planning 2013

Full Report: What’s Happening in Planning 2013

Part I – Introduction

Part II – Overview of City Planning in Los Angeles

Part III – Recent Accomplishments

Part IV – What’s Happening in 2013-14

/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_image/image/61719191/shutterstock_180256895.0.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13248739/shutterstock_127662542.0.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13248829/shutterstock_755896681.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13248847/shutterstock_634308593.jpg)

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/13248965/shutterstock_1045856305.jpg)